As the end of her college program in audio engineering neared, Daehani Mpoyi started looking for a one-bedroom apartment to rent in Toronto.

One day in late 2019, at the beginning of her search, she went to see a unit that seemed to match her needs, she says. She had arranged to go check out the apartment just the day before, but when she showed up for the viewing, she says the landlord inexplicably told her the room had already been rented.

Suspicious, Mpoyi, who is Black, asked a white girlfriend to see if she could schedule another visit.

The friend heard from the same landlord that the unit was still available and had no trouble getting a viewing, Mpoyi says.

“That was one of the first instances I’ve seen of discrimination,” she says of her house-hunting experience.

Mpoyi’s experience is not uncommon in cities like Toronto.

In a 2008 case before the Ontario Human Rights Commission, the Housing Help Centre, a Scarborough-based non-profit, indicated that “(p)eople of African descent have difficulty finding housing because landlords believe they are criminals or have too many children.”

The Commission also heard of other stereotypes, such as the belief that Black Canadian tenants are more likely to be involved with drugs or be violent.

It’s why some Black tenants turn to Facebook Groups such as Black Housing Directory (Renting While Black) Toronto to avoid discrimination.

Lack of discrimination data in Canada

But testing for landlord bias the way Mpoyi did remains virtually unheard of in Canada.

Done by researchers, it’s what urban geographers call “paired testing.” And when it comes to measuring discrimination in housing, “it’s the gold standard,” says Joe Darden, a professor of geography at Michigan State University who has studied the issue on both sides of the border.

The idea is simple. First, analysts select two volunteers with similar characteristics (such as gender, occupation, family status, income, etc.) except for the one to be tested for discrimination. Then, both candidates apply for the same rental unit and closely monitor the treatment they receive. Finally, they compare notes.

In the U.S. the Department of Housing and Urban Development regularly conducts large-scale studies using this methodology, while a number of non-profit agencies use paired testing to produce smaller but more frequent analyses, Darden says.

Litigation over housing discrimination in the U.S. often relies on data from paired testing, he adds.

Canada, however, “has had a problem doing that,” Darden says.

“There is no government agency, based on my research, that engaged in that,” he adds.

While the U.S. often fails to address the discrimination issues highlighted by the wealth of data it collects, “we Canadians don’t want to know,” says David Hulchanski, a professor of housing at the Factor-Inwentash Faculty of Social Work, University of Toronto.

Paired testing, which is expensive and time-consuming, has failed to attract funding at both the government and university level, he adds.

But what little data exists suggests anti-Black racism is a significant problem in Canada’s housing sector.

One report from the Centre for Equality Rights in Accommodation found that Black single parents, along with South Asian households, have a one-in-four chance of encountering moderate to severe discrimination when inquiring about apartments for rent in Toronto.

The study, which dates back to 2009, is a rare example of Canadian research using paired testing.

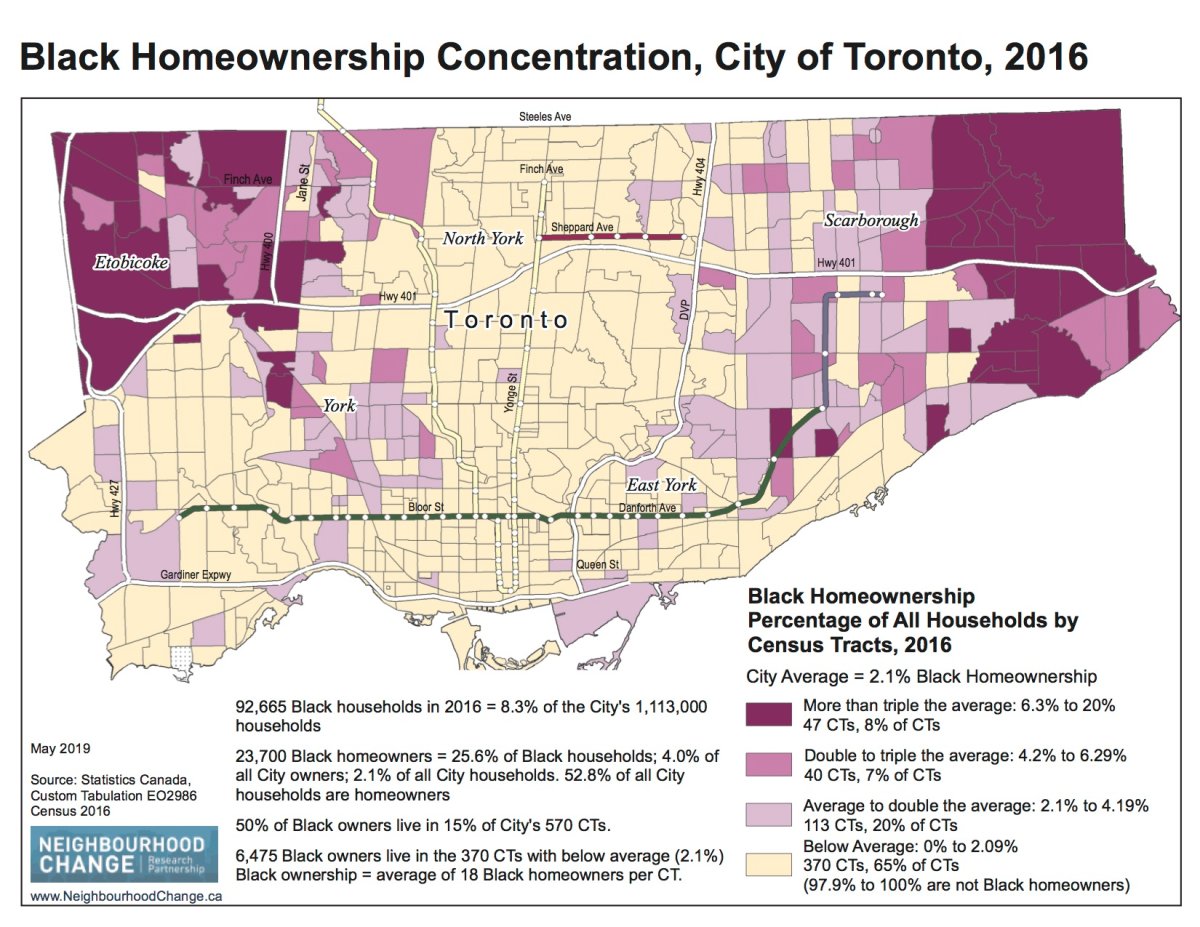

Census data also shows significant segregation of Black households in both the rental and property market. One analysis of the 2016 census data by the Neighbourhood Change Research Partnership, for example, shows Black tenants and homeowners in Toronto tend to live in just a handful of areas in the Greater Toronto Aerea.

“What explains this segregation?” asks Hulchanski.

“‘Black’ is not one ethnic or religious group,’ he noted via email. “The concentration of Toronto’s Black population is thus not an ‘ethnic neighbourhood’ by choice (e.g., Little Portugal),” he wrote.

In a presentation he gave in February, Hulchanski estimated the degree of Black segregation in Toronto is comparable to that seen in Minneapolis, which came in at number 40 in a Brown University study that ranked the 50 U.S. metro areas with the largest Black population from the most to the least segregated.

Later in the year, Minneapolis would make headlines worldwide as the killing of George Floyd in police custody ignited mass protests against anti-Black racism and police brutality around the globe.

Canadian data on racial segregation demands further analysis, but the lack of paired testing means researchers have little insight into the behaviours that lead to that final outcome, Hulchanski says.

Discrimination comes in many forms

Refusing to rent to prospective tenants based on considerations about race, disability, socio-economic status or other factors is just one form of discriminatory behaviour paired-testing research has revealed, Darden says.

Other, more veiled, forms of discrimination may include imposing unequal rent, fees and leasing requirements, or subjecting tenants to different degrees of scrutiny.

The latter is a familiar issue for Andray Domise, a contributing editor to Maclean’s magazine.

Domise, who is Black, recalls being asked by a rental manager whether he was receiving social assistance during an apartment tour in mid-town Toronto in late 2015.

“It was the strangest question for someone who’s wearing a suit and tie,” Domise says, adding that he’d gone to the viewing straight from work.

At the time, he says, he simply stopped filling out the application and left.

“It’s not really worth the argument,” he recalls thinking.

But the episode, as well as other, more subtle instances of possible discrimination, left him feeling wary.

“It was nothing that was that overt,” he says. “But there’s always going to be those ambiguities where you wonder whether you were turned down or whether you were not called back because you showed up and you look different than they expected.”

Another common form of discrimination is known as “racial steering.” In the rental market, it happens when landlords show different units to prospective tenants of different racial backgrounds, Darden says.

“They may show the Black potential tenant in the west wing, and only show the white tenant in the east,” he says.

In the property market, paired testing has shown that real estate agents may “steer” prospective buyers toward specific neighbourhoods based on their race or ethnic background, Darden adds.

And residential segregation, in turn, can perpetuate inequalities by making it harder to find better housing, some research shows.

“Some landlords are influenced by the stereotypes when cued by an applicant’s address in a stigmatized neighbourhood,” Darden and Hulchanski wrote in a 2002 research report they co-authored with Sylvia Novac and Anne-Marie Seguin.

The same can happen when employers spot certain addresses on a job candidate’s resumes, according to Domise.

“I’ve seen a manager take a resume from somebody, have a brief glance at (it), see where the person lived and then write one one zero on it,” he says recalling a Toronto store where he worked in his early 20s.

When he asked about the cryptic one one zero code, the manager drew a diagonal line to connect the two one’s to form the word “no.”

“He didn’t want somebody who came from that neighbourhood working in the store,” he said.

As for Mpoyi, finding a job hasn’t done much to open doors the rental market, she says.

Mpoyi, who says she currently lives in a shelter and put herself through college while couch-surfing and living in transitional housing, landed a position as a warehouse associate in May, despite the COVID-19 pandemic.

She has since stopped showing landlords social assistance cheques as part of her income after getting the impression this was hurting her chances, he says. She has also paired up with a girlfriend, who is also Black.

The two have experienced several instances in which landlords abruptly stopped returning calls or emails just hours after an in-person viewing.

“I’m trying to look for a place to better my life,” she says. “But I’m not even being given a chance simply because of my past and my skin colour and my socioeconomic status,” she adds.

“I don’t even have a chance to be a good tenant.”

Comments